Rhythm is an important aspect of music and life. Much of our experience is based upon rhythmic patterns (sleep/wake, morning/night, in/out, up/down, etc.). In music, rhythm is a basic building block of pattern and structure. We will learn rhythmic patterns from their beginning elements and progress to more advanced analysis and listening.

- Rhythm: “the pattern of regular or irregular pulses caused in music by the occurrence of strong and weak melodic and harmonic beats.”

Below are review pages regarding music notation and rhythm.

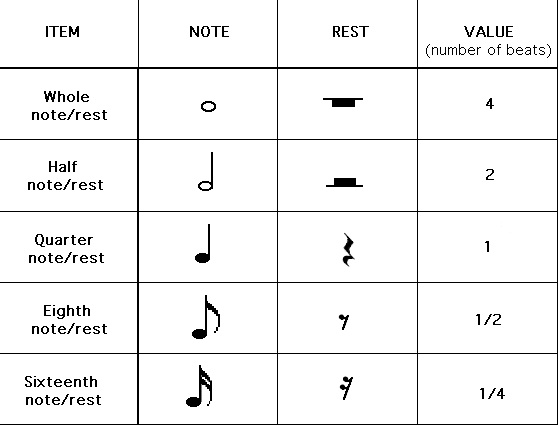

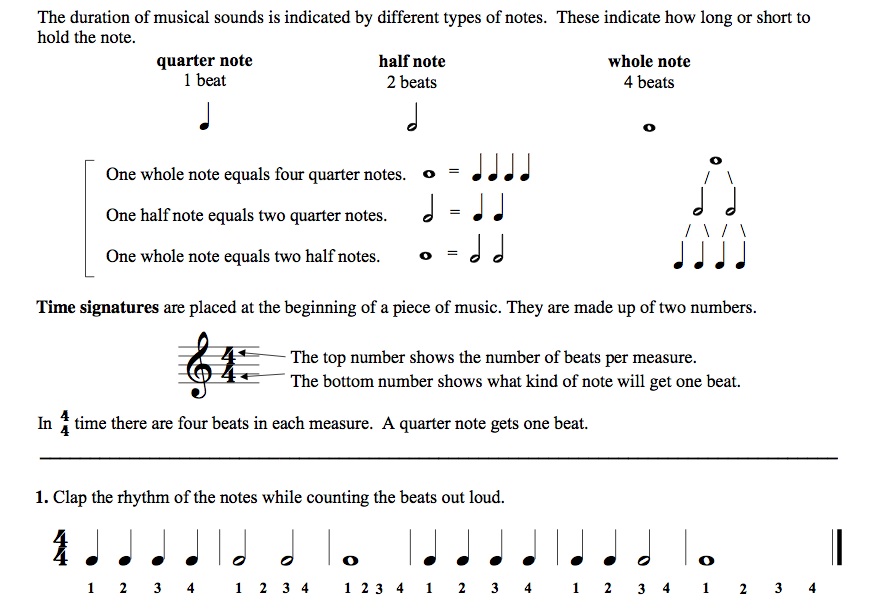

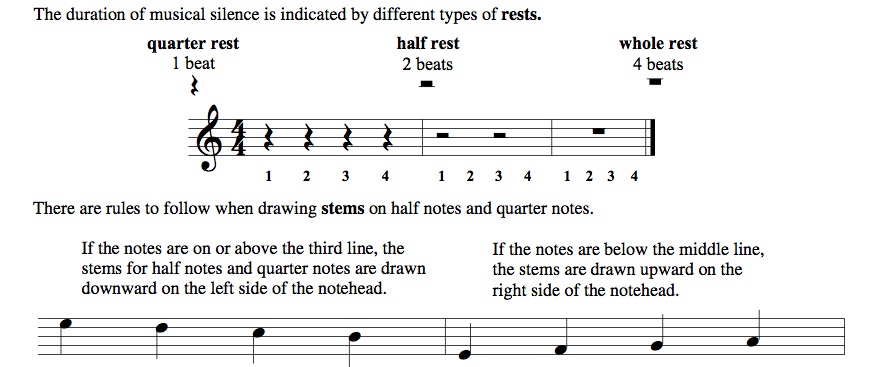

Note Value Review

Rhythm, Meter, Tempo, and Syncopation

|

||

Rhythm is the time aspect of music or the way sound in arranged through patterns of time. In many ways we feel rhythm in our heartbeat and when we breath and walk. There is also a sense of rhythm in the recurring pattern of day and night, the four seasons of the year and the rise and fall of the tides. In music it occurs in patterns of tension and release and in through musical expectation and fulfillment.

|

||

The basic recurring unit of time in music is beat. A beat is the physical part of the music that makes us tap our toe, clap our hands or move our body. Beats form the background against which a composer or musician place notes of varying length. Expression is felt right away by rhythm. How we hear the beat can tell us if a piece of music is a march, a dance, a forceful powerful gesture or a gentle flowing elegance.

| |

|

||

An accent is when a note or group of notes are emphasized or played more loudly then notes around it. An accent can be felt or heard. A sound can be emphasized, (or accented) by being held longer , by being higher in pitch than nearby notes or simply played stronger (or louder) than surrounding notes. The most straightforward way to play an accent is to alternate between one accented count and one unaccented count. A strong beat followed by a weak beat. ONE – two, ONE – two.

| |

|

||

A group of beats that are defined by patterns of strong and weak pulses is called meter. Meter can be felt or heard. It is when a strong accented beat (usually the ONE or first beat of the pattern) is followed by one or more weaker beats. This forms a recurring pattern in music. The two basic beat patterns or meters in music are duple and triple. An example of duple meter is a march, where the LEFT – right – LEFT – right, is best represented by STRONG – weak, STRONG – weak. An example of triple meter is a typical waltz, ONE – two – three, ONE – two – three or the tune to Clementine, OH my dar ling, OH my dar ling.

Duple Meter

ONE – two – ONE – two – etc.

Two additional meters found much less frequently in music, are compound meter and mixed meter. In compound meter you have more than one meter at the same time. For example a simultaneous occurrence of duple and triple. 1 2 3 4 5 6. In mixed meter, two opposing meters happening one right after another. For example Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” 1 2 3 4 5. “Take Five” is an example of a triple meter followed by a duple.

Compound Meter

ONE – two – three – FOUR – five – six – etc.

Mixed Meter

ONE – two – three – FOUR – five – etc.

|

||

One way composers and musicians spice up the rhythm and give the music a sense of surprise and uplift is by adding what is called syncopation. Syncopation is when a normally weak beat produces an emphasis. Syncopation is putting the accents off the beat. A lot of jazz syncopation puts the accents on the “ands” in-between the beats rather than putting the accent on either the strong or the weak beats. One – two – AND – three – four – AND .

Straight meter Syncopation

ONE – two – THREE – four – one – TWO – three – FOUR

Another way to think of it is:

Straight

NOTHing COULD be FINer THAN to BE in CAroLINa IN the MORning.

Syncopated:

noTHING could BE finER than TO be IN caROlinA in THE morning.

|

||

The rate of speed at which a piece of music is to be played or sung is called tempo. Choosing the right tempo for a musical composition is one of the most important factors in making a work musical and meaningfully coherent. Traditional tempo marks are given in Italian and leave considerable freedom to the performer. They are as follows:

|

Largo, Lento Very Slow |

|

| Adagio Slow | |

| Andante Moderately slow (at a walking pace) | |

| Moderato Medium | |

| Allegro Fast | |

|

Presto Very Fast

|

In a classical composition, up until the Romantic era (1828), tempos were often the titles for compositions or movements from larger works. Because tempo marks such as Allegro or Andante leave substantial room for variants of fast or moderately slow, a performer can be guided by a metronome. A metronome is a type of mechanical clock that beats time. It can pulse out various beats at exact divisions of time. It is calibrated for clicks per minute and depending on what setting it is placed it will beat time from 40 beats a minute to 208 beats. It was invented by Johannes Maelzel in 1813. Maelzel was a friend of Beethoven and he was one of the first important composers to place exact metronome marks in musical scores.

We associate fast tempos with energy, drive and excitement and we associate slow tempos with solemnity, lyricism or calmness. This is because of our standing heart beat is from 60 to 75 beats a minute. Any beat faster or slower than our heart beat we perceive as fast or slow.

|

Largo, Lento – 40-52 (beats per minute) |

|

|

Adagio – 54-66 |

|

| Andante – 69-76 | |

|

Moderato – 76-112 |

|

|

Allegro – 116-160 |

|

|

Presto – 168-208

|